Voyage to Nowhere

There have been ocean rallies, regattas and races but as a sailing event, the Moruroa anti-nuclear flotilla protest has few precedents. Usually, there’s a destination, a welcoming committee, somewhere to rest ashore, relaxing bars and restaurants. At Moruroa there’s an exposed patch of ocean, no supplies of food or water, nowhere to repair damaged parts and the only welcome is from the French Navy, offering arrest and seizure of any vessel approaching within 12 miles of the atoll.

Flotilla crews.

Even with the promise of an arduous passage and the need to take 4 months unpaid leave from work, there were more people wanting to take an active part in the protest than there were crew spaces available. However, moral indignation against nuclear testing is hardly a substitute for seagoing experience so skippers needed to be especially careful in appointing crew positions. With so little time available there were few chances for crews to get used to living and working together. Incompatibilities were a problem for a few boats and for one, an unplanned diversion to Rarotonga for repairs, provided the chance of a crew change that was heartily welcomed by all involved. But in any sailing event of this type such social problems are to be expected and for most were largely ironed out once the destination was reached.

To take part in the protest action, Zohl Ishta had travelled from Australia to join the trimaran Triptych. A few years previously she had taken part in a woman’s camp on Greenham Common in the UK protesting against US cruise missile sites. “After camping out for 5 UK winters, sailing the Pacific can surely not be so bad?” she felt. Though other flotilla crews certainly shared strong feelings against nuclear testing, for many this was the first time they had actively joined a protest demonstration.

The route.

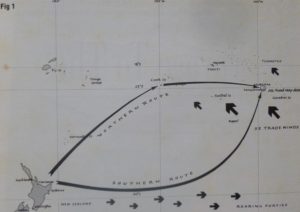

5th August, Hiroshima day, marked the official departure of protest boats from Auckland. Like a Whitbread send off, the event was attended by hundreds of well-wishers and ahead lay a journey of at least 2600 miles, similar in distance to an Atlantic crossing, with every possibility of bad weather for some of the time. During the planning stages, one or two skippers considered breaking the voyage by sailing north early and calling at Rarotonga and Tahiti. The difficulty with this option is that it involves beating against the south east trades that can be particularly strong at this time of the year. The few that took this option put in many hours of motoring and did so because they needed to stop off for repairs or exchange crew.

For sailing boats, a more practical option is to remain south of 37 degrees south close to the ‘Roaring forties’ where winds are more likely to be from the west. Unfortunately, the regular succession of low pressure systems following the same path is likely to bring strong winds and rough seas from any direction. The first boats to leave certainly had their share of heavy weather but, as luck would have it, winds were often from astern and many achieved much faster passage times than they expected. Later boats such as the Anna were less fortunate. As the skipper, Lars Forberg reported “The book ‘Ocean Passages for the World’ advised that we could expect 5 days of bad weather in 30 – in the 30 days we saw only 5 days of good weather.” Even when winds were from astern, they were occasionally too strong for comfort and safety so at one stage the boat’s speed was reduced by towing a warp attached to tyres and chains.

Fig. 1 The route: New Zealand to Moruroa.

In the event of intolerably bad weather or other difficulties the nearest refuges to Moruroa are the Gambier islands, 230 miles to windward or a 600 mile down wind run to Tahiti. As anti nuclear protesters, yachts calling at these islands were at first unsure of the kind of welcome they might receive but all fears proved to be unfounded. In the Gambier islands, shortly after the Tahiti riots, Lars Forberg reported a rapturous reception. Port formalities proceeded smoothly and their short stay included a busy round of social invitations ashore for coffee, showers, dinners, television and walks around the island.

In Tahiti, clearance through the normal official channels is seldom speedy at the best of times. Usually you have to queue at several offices and negotiate payment of the infamous bail bond. This involves the payment of an amount equivalent to an air fare back to your country of origin and is a much hated regulation that’s not evenly applied across the board. None the less, most protest boats did not feel they had been treated any more harshly than other visitors and some reported VIP treatment from the locals with gifts of fruit, groceries and eggs. So many eggs that omelets, fried eggs, poached eggs, boiled eggs and soufflés appeared on the menu for weeks to come.

A village in mid ocean.

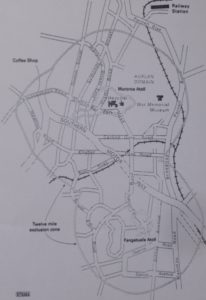

The 12 mile exclusion zone declared by the French for the duration of nuclear testing encircles the twin atolls of Moruroa and Fangataufa. To discourage intruders, the area is heavily patrolled by warships and aircraft, who are able to monitor the area with radar and infra-red image enhancing equipment. Foreign vessels sailing into the zone risk prompt arrest and seizure so for most of the time boats had to be content with sailing around its 160 mile perimeter or meeting at a favourite spot off the North west corner known as the “coffee shop.” This had the advantage of being close to Moruroa’s entrance channel so ships entering and leaving could be easily observed and, since it was down wind, protest boats were not at risk of inadvertently drifting into the zone.

“We came in from nothing and found a floating village” said Denis Johnson aboard the yacht Joie. “It became like home; we visited people, had parties and barbecues.” To add to the illusion, some boats used a chart of Moruroa overlaid with a road map and referred to positions by road names. Initially, the idea was to conceal tactics from French radio monitors, though it was never widely used for this purpose. Instead it added a homely touch to a hostile environment and reports of “shopping in Queen Street” or “cruising along ‘K’ road” (Auckland’s Red Light District) took on a whole new meaning.

At 12 miles, the atoll provides no shelter from ocean swells, and the only evidence of land are a few distant towers and buildings, with the loom of lights at night. It’s a lonely, featureless spot and to stay close to one place requires constant attention to navigation and sailing against the trades. Typically, yachts would move in close to the leeward side of the atoll in the evening, then spend the night drifting down wind at about one knot. It was all too easy to lose ground and if the winds were strong, much of the following day might be spent beating back on station.

Silent sentinel or white knight?

The New Zealand government’s decision to send a navy vessel to support the flotilla was not fully understood until HMNZS Tui was actually on station at the atoll. In fairness this was, to say the least, an unusual role for a vessel that is technically a warship. The official objectives were to show New Zealand’s concern over the French decision to resume nuclear testing and to provide logistical support for the protest flotilla. In practice, its effect depended on being able to offer a prompt and appropriate response to a range of events that, at the outset, were impossible to predict.

Prime Minister Jim Bolger described the ship as a ‘silent sentinel,’ yet for the news media it was anything but silent since it carried several journalists, a television team and was equipped with two INMARSAT communications terminals. For protest boats it was a huge moral boost simply to see the Tui appear over the horizon, meaning that there would at least be other witnesses to any French action. Even non New Zealand vessels appreciated its presence though, except in an emergency, the Tui was only authorized to provide material help to New Zealand flotilla boats.

On the whole, flotilla boats were well prepared for their stay at Moruroa though the length of time any small boat can remain at sea is obviously limited by its capacity to carry fresh water, food and fuel. Both Tui and the Greenpeace vessel Machias working out of Tahiti, helped with the job of re-supplying boats with vital stores. Tui provided fresh water to almost every flotilla boat and a few also needed fuel, small repairs and medical assistance

.

… and then there were none.

In recognizing the right of the French to declare and enforce the exclusion zone around Moruroa and Fangataufa, the New Zealand government did not wish to support boats that willfully breached it. Assurances from flotilla boats that they did not intend to enter the zone were initially sought and, except for emergency help, the offer of assistance was withdrawn from those who went back on the agreement. At times, this presented a considerable dilemma to the Tui’s captain, Lt. Cdr. John Campbell. When yachts occasionally seemed to drift into the zone, was it a momentary lapse of attention, faulty navigation, engine failure or part of a plan to land personnel on the atoll? For the most part, the French took a lenient view on minor transgressions, but Greenpeace boats entering the zone or even launching dinghies that later entered the zone, were promptly boarded, seized and crews flown out.

The day the bomb went off

It was a typical tropical day with light winds and fluffy trade-wind clouds.

The crew of the Greenpeace boat, Manitea, has recently been arrested and I am spending the morning recounting events aboard the flotilla boats, Gemini Galaxsea and Sudden Laughter.

A turbo prop aircraft takes off from Moruroa and heads off towards Tahiti. We presume it has the Manitea crew aboard. In addition to the usual low-level fly past by a Lear jet, French military activity is heavier than usual with two warships circling the flotilla.

Shortly after lunch I return to the Tui aboard the ship’s fast Rigid Inflatable and soon hear a radio message from the Anna relaying a message from Greenpeace, Tahiti, saying that the second nuclear test has taken place.

About 50 miles away beneath Fangataufa a 96 kiloton device has been exploded, yet none of us noticed. No mushroom cloud, no flash, no bang, no Electro-Magnetic Pulse destroying radio equipment, no sound through the air or water. No-one noticed except maybe the three white tip sharks that appeared circling the Tui that same afternoon. Or perhaps the Humpback whale that surface off the port quarter and made off towards the entrance to the atoll.

In the first few weeks of the campaign when Greenpeace vessels MV Greenpeace, Rainbow Warrior, Manitea and Vega were in the area, active protests and maneuvers occurred every 3 to 4 days. However, by the end of September the French had discovered reasons to arrest all Greenpeace vessels and remove them from the scene. The second blast left the crews of the remaining boats Anna, Gemini Galaxsea, Guinevere, Sudden Laughter and Te Kaitoa angry and deeply despondent. As a final gesture before leaving the atoll a ceremony was held in which all boats gathered on the edge of the zone for the symbolic release of balloons, paper cranes and to deliver speeches to French radio monitors. Over the following weeks more are scheduled to arrive at Moruroa though with the cyclone season officially open from November 1st, it seems unlikely that large numbers will take their place

Bombs are still being tested so was it all worth it?

“Unreservedly yes” was the general opinion. While the French have only conceded a small reduction in their test programme, it is believed that they severely misjudged the enormous strength of opposition to the testing. In being at the focal point of such strong opposition most feel they have made a useful contribution to creating a climate where the development of nuclear weapons is politically unacceptable.

.